The 1920s was a time of rapid social and economical change between the wars. Artists used their mediums as a way to express their views on the change society needed.

Josephine Baker was one of these influential figures.

(Gaston Paris/Roger Viollet, 1926)

credit: gettyimages

(ullstein bild, 1908)

credit: gettyimages

Josephine Baker was born, Freda Josephine McDonald, on June 3rd 1906, in St. Louis, Missouri.

Baker grew up in an impoverished family. Her mother, Carrie McDonald, was a washerwoman and her father, Eddie Carson, was a vaudeville drummer. He abandoned Baker and her mother, shortly after her birth.

To support her family, Baker began working as a maid at age eight and by age fourteen, she had left home and separated from the first of five husbands.

Taking influence from her mother, who had given up her dreams of becoming a music-hall dancer, Baker learned to dance. She performed in streets and clubs, and by 1919 she was touring the states with the Jones Family Band and the Dixie Steppers; performing comedic skits.

In 1921, she adopted the name Baker when she married Willie Baker; she continued to use his name even though they later divorced.

In 1923, Baker landed a role in the musical ‘Shuffle Along’, Broadway’s first Black musical. The comedic touch that she brought to the role made her stand out and steal the show.

Looking for more opportunity, Baker moved to New York City and was soon performing in ‘Chocolate Dandies’ in the floor show of the Plantation Club, where she quickly became a crowd favorite.

(Emil Bieber/Klaus Niermann, 1925)

credit: gettyimages

In 1925, at nineteen years old, Baker moved to France with the black American vaudeville troupe ‘La Revue Nègre’.

In her autobiography, (Baker and Bouillon, 1977) Baker describes the outfit she wore, when arriving in Paris, as awkward, gaudy, and out of place. Josephine visited Paul Poiret, who replaced the homemade Harlem outfit with a silver satin gown.

For many years, Poiret, (aka, the father of the 1920s flapper movement) remained one of Baker’s primary dress designers along with Vionnet and Schiaparelli.

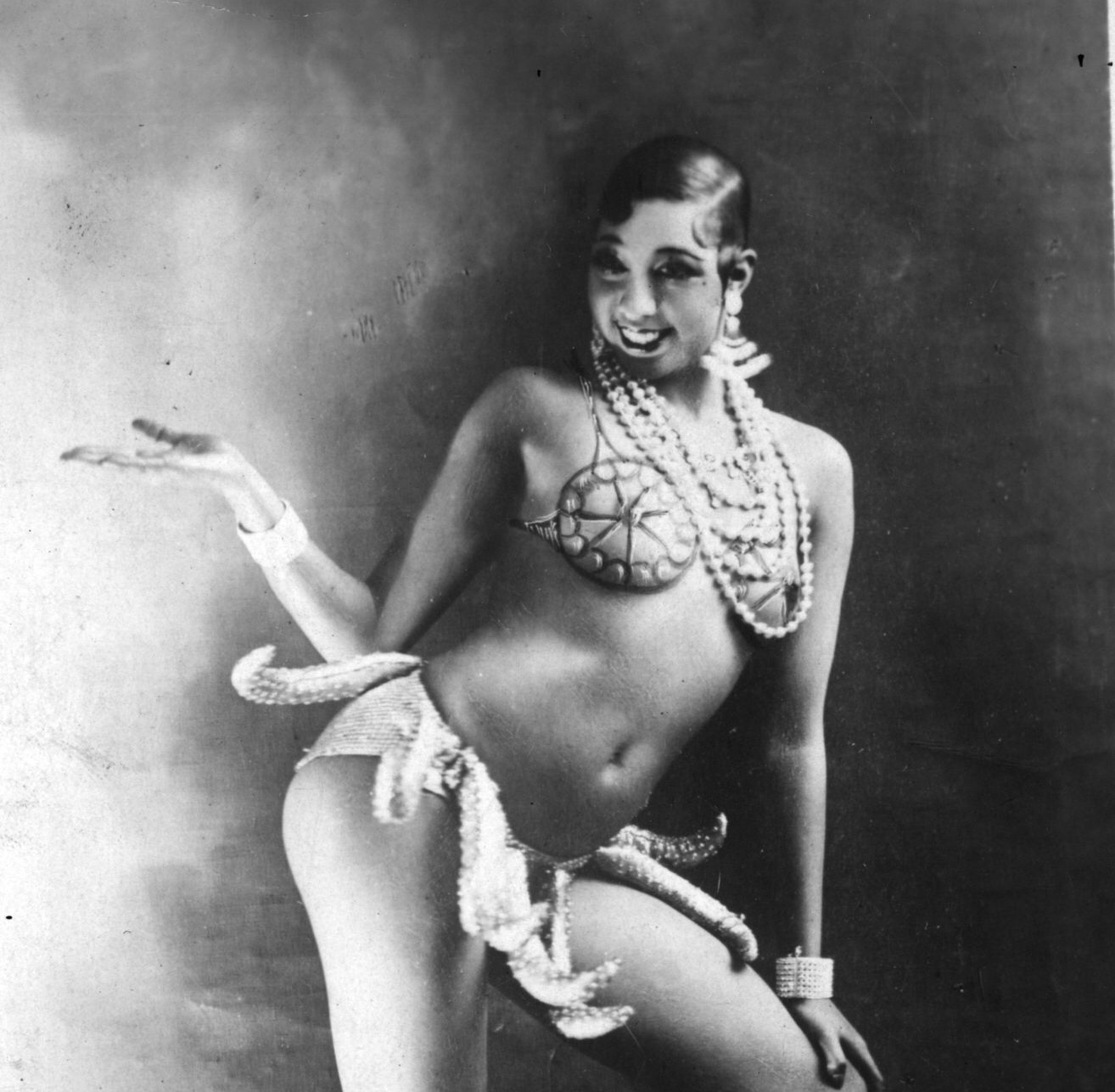

(Walery, circa 1926)

credit: gettyimages

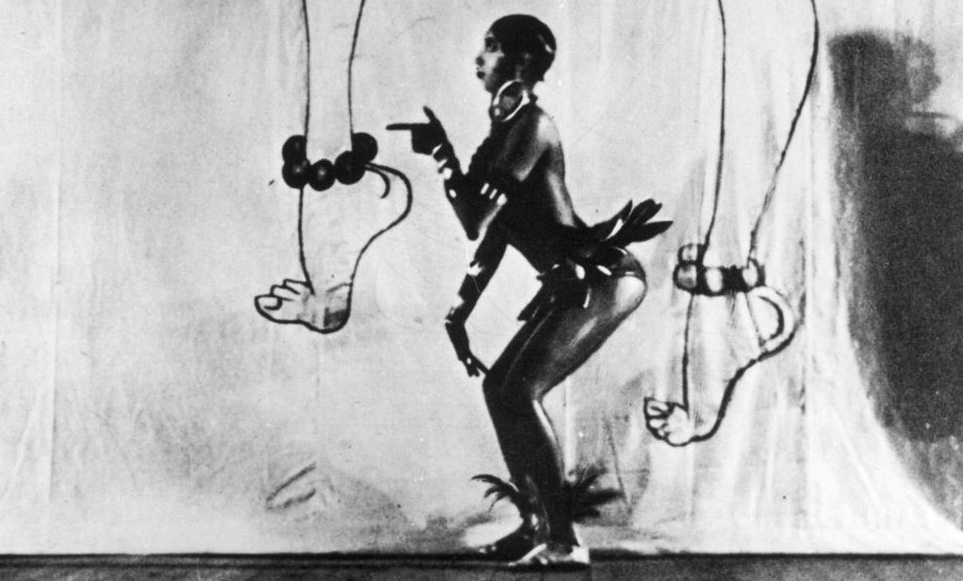

In France, Baker was an immediate success with her ‘Danse Sauvage’, which she performed in only a skirt of feathers.

1925

A year later, at the Folies Bergère music hall, Baker danced ‘La Folie du Jour’ in the renowned banana skirt. The dance was uninhibited and controversial, turning her into a star overnight.

1926

Baker’s performances created a fantasy for her western audience.

She played to the preconceived, western stereotypes of black women, and used it to her advantage.

She performed primitive, African influenced dances, exaggerated by the exotic and provocative costumes she wore.

(Hulton Archive, 1929)

credit: gettyimages

(Hulton Archive, circa 1930)

credit: gettyimages

(Bettmann, 1928)

credit: gettyimages

As her success grew, Baker transformed her theatrical performances into social and political statements.

(Popperfoto, circa 1929)

credit: gettyimages

Baker manipulated the controversial images that were predetermined for her, in both her performances and her everyday life.

As many of Baker’s early followers belonged to the Parisian demimonde, she explored using transgender imagery in her work. This appealed to the young, tuxedo-clad women who admired her.

While in public, Baker enjoyed playing her stage characters of the sexualized savage, the male-female, and the saint-like Madonna.

(Roger Viollet, 1926)

credit: gettyimages

Through the 1920s, Josephine Baker became one of Europe’s most popular and highest-paid performers. She was admired by figures such as Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway and E. E. Cummings.

(Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone, 1928)

credit: gettyimages

(Hulton Archive, 1936)

credit: gettyimages

In 1936, on the back of her success in Paris, Baker returned to the US. She performed in the ‘Ziegfeld Follies’.

Baker had hoped to establish herself as a performer in America, but was regrettably met with hostility and racism.

She soon returned Paris, acquired a French citizenship and lived there for the rest of her life.

During World War II, Baker was a special agent and French Air Force sub lieutenant.

(John D. Kisch/Separate Cinema Archive, 1944)

credit: gettyimages

(Keystone/Hulton Archive, 1945)

credit: gettyimages

Baker was awarded both the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour with the rosette of the Resistance, two of France’s highest military honors.

Like a number of African political leaders, her military uniform became a symbol of her status the leader of a humanitarian social and political cause.

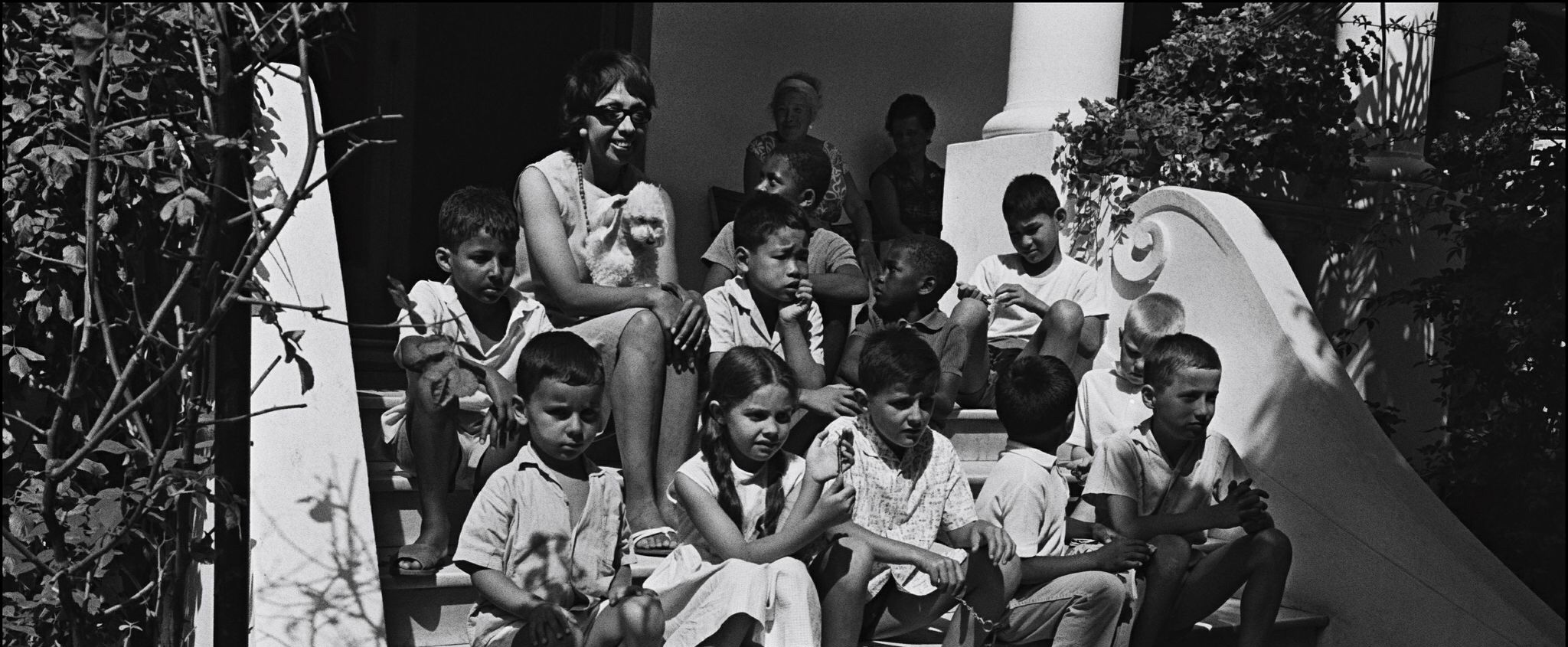

(Photo by Georges Menager/Paris Match, 1961)

credit: gettyimages

Soon after the war, Baker toured the United States again, and this time she won respect and praise from African-Americans for her support of the Civil Rights Movement.

(Alfred Eisenstaedt/The LIFE Picture Collection, 1951)

credit: gettyimages

In 1951, the NAACP named her ‘Most Outstanding Woman of the Year’ for her efforts.

She gave a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall for the NAACP, the SNCC, and CORE in 1963 and was the only woman to speak at ‘the March on Washington’.

The NAACP named May 20th “Josephine Baker Day.”

(Francis Miller/The LIFE Picture Collection, 1963)

credit: gettyimages

“You know I have always taken the rocky path, as I get older, and as I knew I had the power and the strength, I took that rocky path, and I tried to smooth it out a little.

I wanted to make it easier for you. I want you to have a chance at what I had, but I do not want you to have to run away to get it.”

-Josephine Baker, April 28th 1963

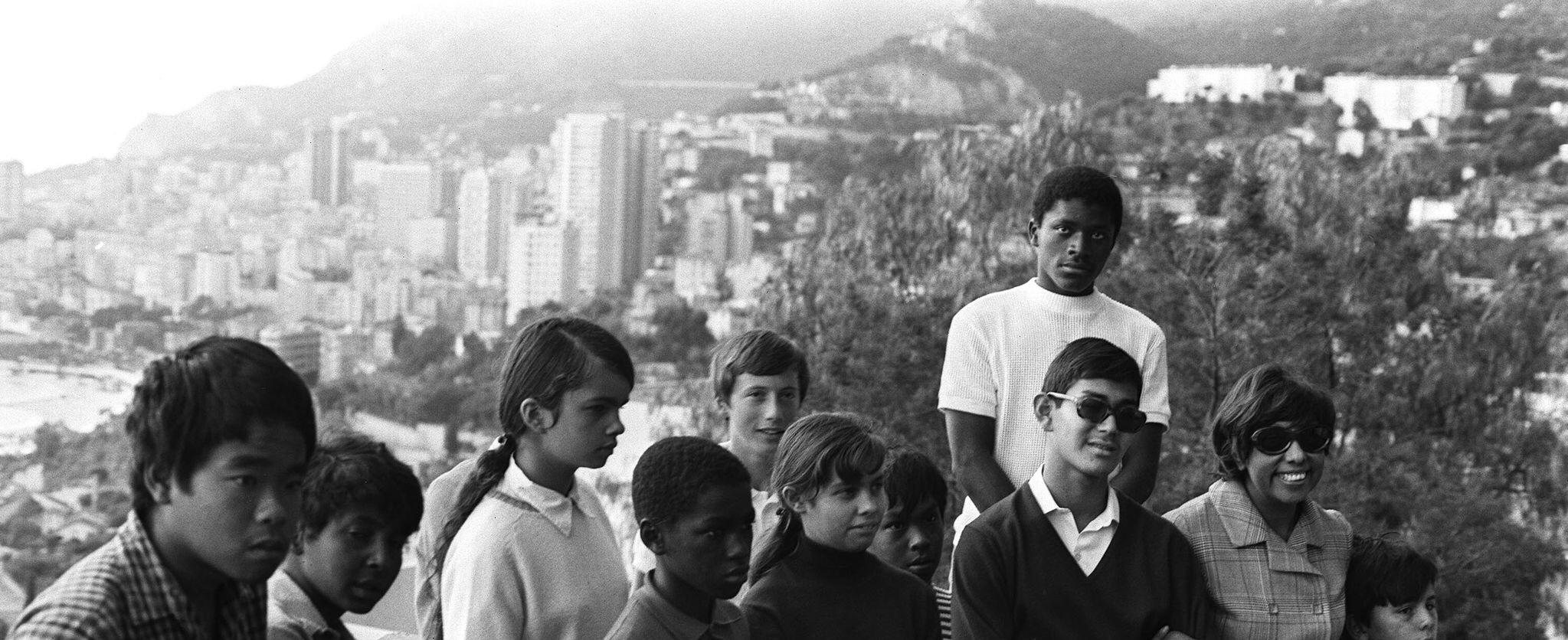

In the 1950s she adopted twelve children of different nationalities and ethnicities. They were named the ‘Rainbow Children’ and lived in the Château des Milandes in southwestern France.

She invited people to see these children, to demonstrate that integration of races is harmless. The children further enhanced her image as the saint-like Madonna.

Although Baker’s maternal image juxtaposed with her earlier risqué image, the picture of ‘the savage dancer and the ‘Black Venus’ worked to secure publicity for her humanitarian work.

(Michael Ochs Archives, circa 1970)

credit: gettyimages

(Daniel SIMON/Gamma-Rapho, 1973)

credit: gettyimages

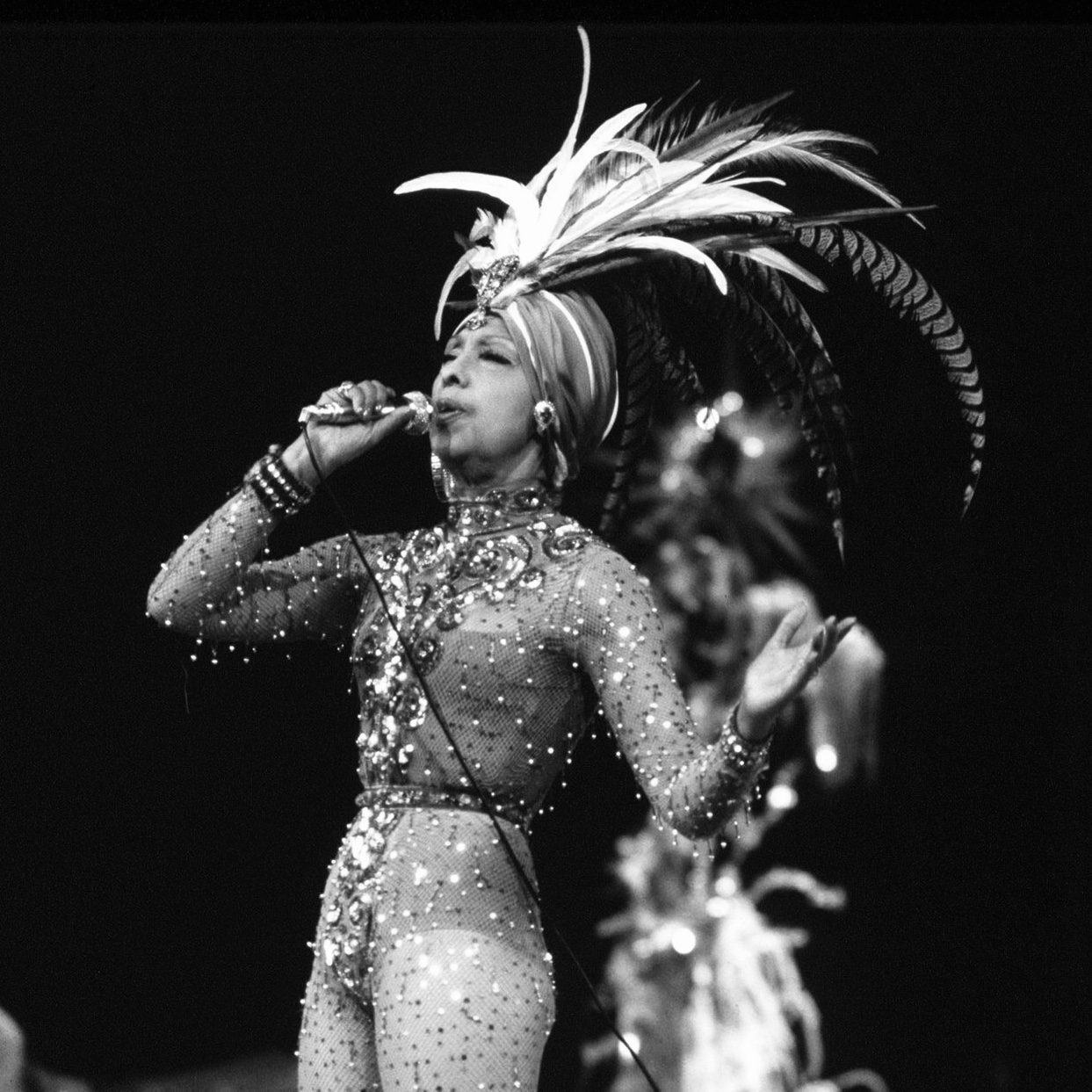

In 1973, Josephine Baker made her comeback to the stage. The 50th anniversary of her arrival in Paris was marked in 1975 with a huge gala in Monaco to celebrate.

(Andre SAS/Gamma-Rapho, 1956)

credit: gettyimages

Unfortunately, four days later, on April 12 1975, Baker died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

On the day of her funeral, more than 20,000 people lined the streets to witness a 21-gun salute, making Baker the first American woman to be buried in France with military honors.

Modern Comparison

Josephine Baker broke boundaries for black women within the entertainment industry. Her success gave future young black women the hope of achieving stardom in the mainstream media.

(Scott Gries, 2006)

Courtesy of Getty Images

When deciding on an appropriate modern comparison to Josephine Baker, I immediately thought of Beyoncé. This is because of the many similarities I found between the two. Like Josephine Baker, Beyoncé is one of the most popular and highest paid performers of her time. In 2017, she was named highest paid female artist by Forbes.

As southern African-American women, their southern and African roots are major influences on their performances. For example Baker incorporated the southern dance ‘The Charleston’ into her performances, turning it into a widely-recognised dance craze. Whereas, Beyoncé used her ‘Formation’ music video to call out police brutality and racism, still evident in previous slave states within the south. Taking from their African influences, Baker’s ‘Danse Sauvage’ was set up to look like it was set in an African jungle with a dancing tribe. Beyoncé’s music video for ‘Grown Woman’ featured African tribe dances and costumes. The video showed comparison between the modern black ‘grown woman’ and her African roots.

Beyoncé has always cited Josephine Baker as a key influence to her performances. This was particularly shown in the music video for ‘Déjà Vu’. Beyoncé performed a dance breakdown inspired by Baker’s ‘Danse Sauvage’ (the banana dance). She danced in Baker’s suggestive, and almost aggressive style of dance, in a bra and mini skirt costume, reminiscent of Baker’s banana skirt.

When performing ‘Déjà Vu’ live at Conde Nast’s third annual Fashion Rocks Concert in 2006, Beyonce turned the performance into a Tribute to Josephine Baker in honour of her 100th birthday. She essentially recreated ‘Danse Sauvage’, wearing a jeweled bra and satin banana skirt.

Beyoncé spoke to ABC News in 2006 about Baker as her inspiration.

“I wanted to be more like Josephine Baker, because she didn’t, she seemed like she just was possessed and it seemed like she just danced from her, her heart, and everything was so free”

Although Baker and even Beyoncé have paved way for other black women within the media. Black women (particularly dark skinned women) still face stagnation in achieving success, compared to other demographics. It raises the question ‘would Josephine Baker and Beyoncé have been as successful as they were if they were not of a lighter complexion?’ Beyoncé father, Mathew Knowles, made headlines recently for stating that his daughter’s light complexion ‘affected her success’, when compared to her darker skinned band mate Kelly Rowland. America has always been very sensitive to race and colour, due to the effects of slavery and segregation.

Josephine Baker had to escape the prejudice of America to achieve her stardom in France, that was much more accepting. Europe loved Baker, but it was because of the fact that she played into their pre-conditioned idea of an African woman, and used it to her advantage. It is alleged hat Josephine Baker’s biological father was white, giving her a light tone. If Baker was darker, I imagine it would have been harder for a nineteen-twenties audience to accept her. Baker being paler, made it easier for the western world to accept her, as black woman, into the mainstream; as it wouldn’t be as a much of a dramatic change.

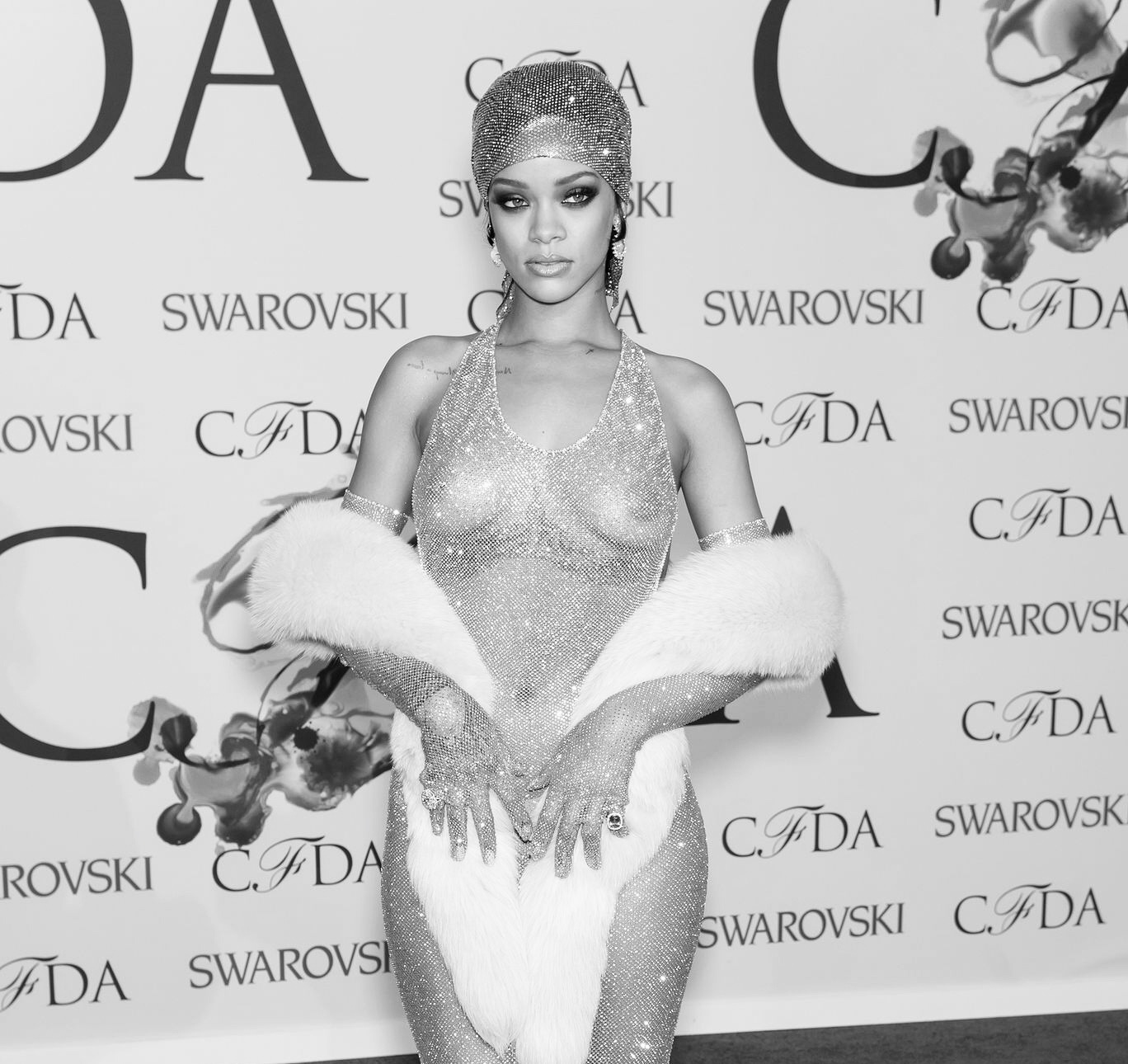

(Gilbert Carrasquillo/FilmMagic, 2014)

Courtesy of Getty Images

Another current black female musician who draws from Baker as inspiration is Rihanna. In 2014, Rihanna caused a stir when she attend the CFDA fashion awards in a see-through, Swarovski encrusted dress. Everyone wanted to find out about the inspiration behind the show-stopping look. Rihanna took to twitter to cite Josephine Baker as the influence, in honour of her 108rd birthday. She tweeted: ‘Happy Birthday to the late Josephine Baker! You have and will continue to inspire us women for decades to come!’

She attached a side by side of her outfit and this picture of Josephine Baker.

(General Photographic Agency, 1928)

credit: gettyimages