The Harlem Renaissance or ‘The New Negro Movement,’ was a cultural movement that peaked in the late nineteen-twenties.

Although the movement was based in Harlem, New York, its influence extended throughout the United States; and even some parts of Europe.

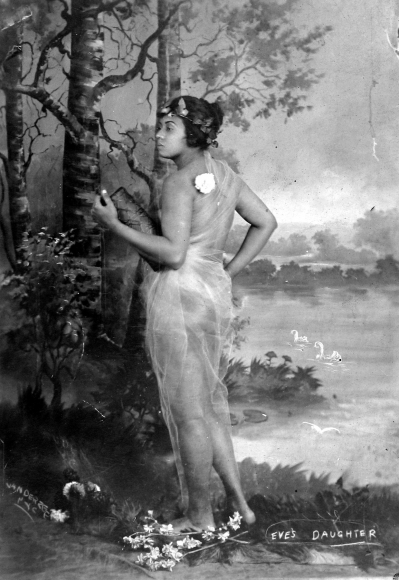

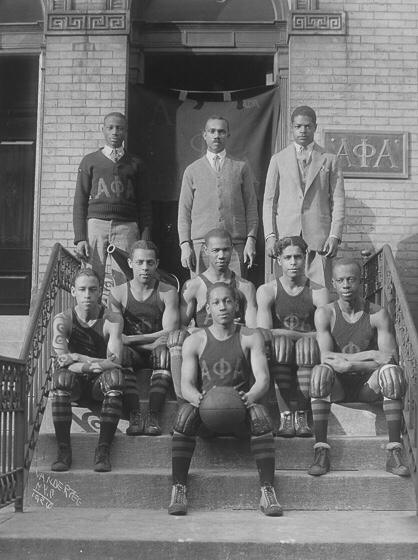

James VanDerZe, 1924

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery

The Harlem Renaissance is considered a golden age in African American culture, as it proudly championed black intellectual and artistic production. It manifested itself in literature, music, stage performance and art; It was a key element of the formation of black modernity. This movement focused on the evolution of freed slaves, incorporating their African heritage into American ideals to create their own identity and place in a civilised society.

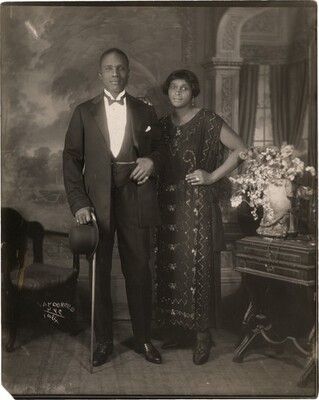

James VanDerZee, 1924

Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery

The social foundations of this movement included the Great Migration. Following the Civil War, large numbers of African-Americans migrated to northern urban areas. From 1910 to 1920, 300,000 African Americans from the South had moved north, and Harlem was one of the most popular destinations for these families.

Alain Leroy Locke

Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1946

Courtesy of Getty Images

Civil Rights activist, Dr. Alain Leroy Locke is often identified as the ‘Father of the Harlem Renaissance’. Having received a PhD from Harvard, and being the first African American Rhodes Scholar to come to Oxford, Locke was one of the key intellectuals behind the Harlem Renaissance.

Having studied African culture its influences on the western world, he encouraged black artists to look to African sources for inspiration and to discover materials and techniques for their work. In his publications, he would argue that, while art could function as propaganda, artists should be free to choose their subjects. Locke recognised European interest in African art as a means of emphasising African-American modernity and black Modernism.

Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery

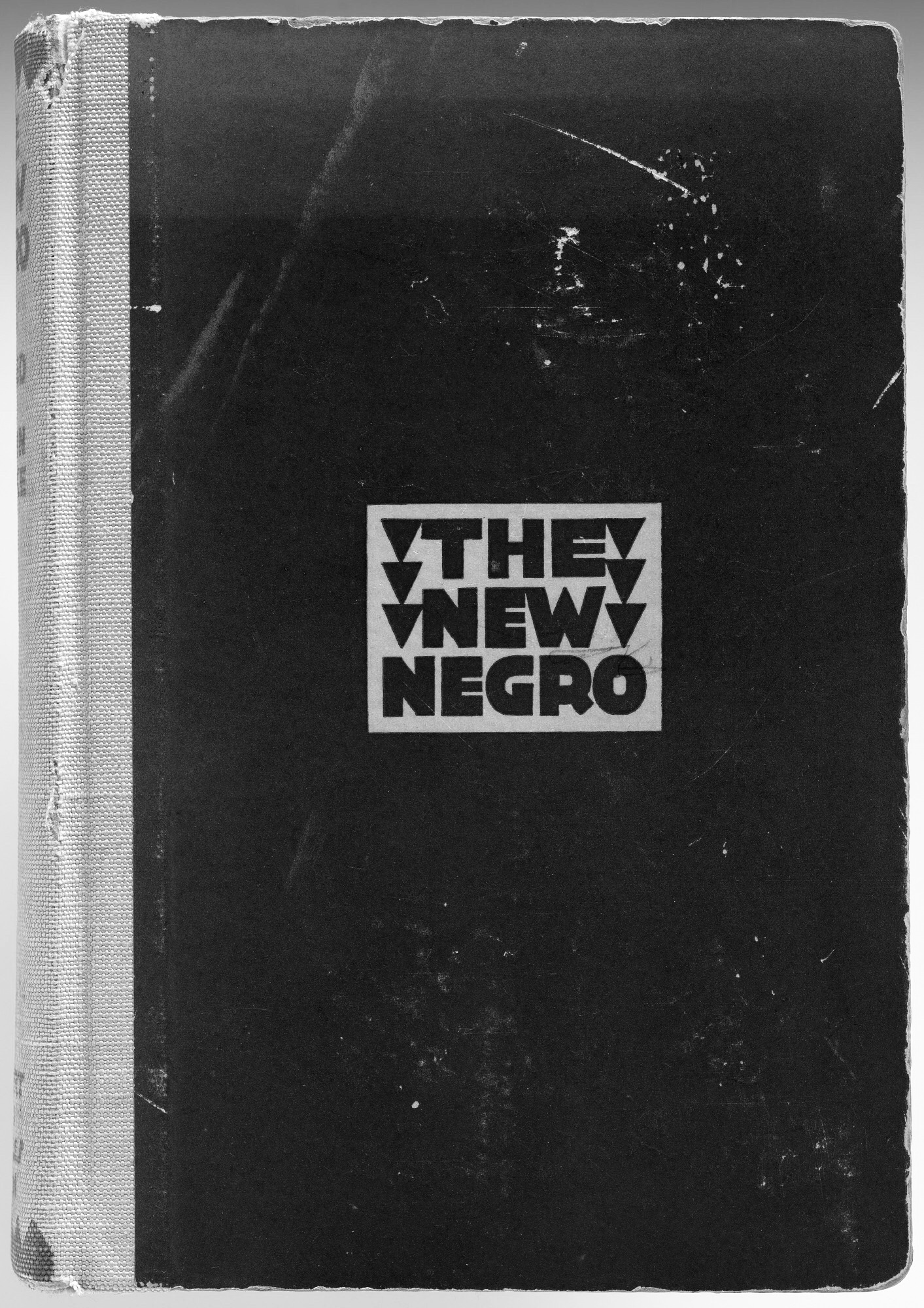

He introduced American readers to the Harlem Renaissance by editing a special Harlem issue for Survey Graphic, 1925, which he expanded into the anthology, The New Negro, 1925.

“Harlem is the precious fruit in the Garden of Eden, the big apple.”

Alain Leroy Locke

Harlem Renaissance Art

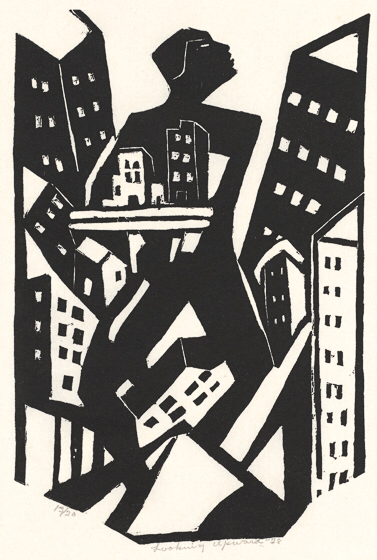

Harlem Renaissance art always had an emphasis on Africa as the origin of African-American culture and often featured bold colors, composed in an expressionist fashion. Many of these pieces portray educated, middle-class, African-Americans dancing, making music, dining or engaging in other past times. As well as that, jungle and tribal scenes were often depicted as a way of honouring African-American heritage. Tribal African imagery was juxtaposed with modern art, resulting in a revolutionary genre that linked African heritage with social advancement. Particularly popular art styles during the Harlem Renaissance include Art Deco, Surrealism, and Impressionism.

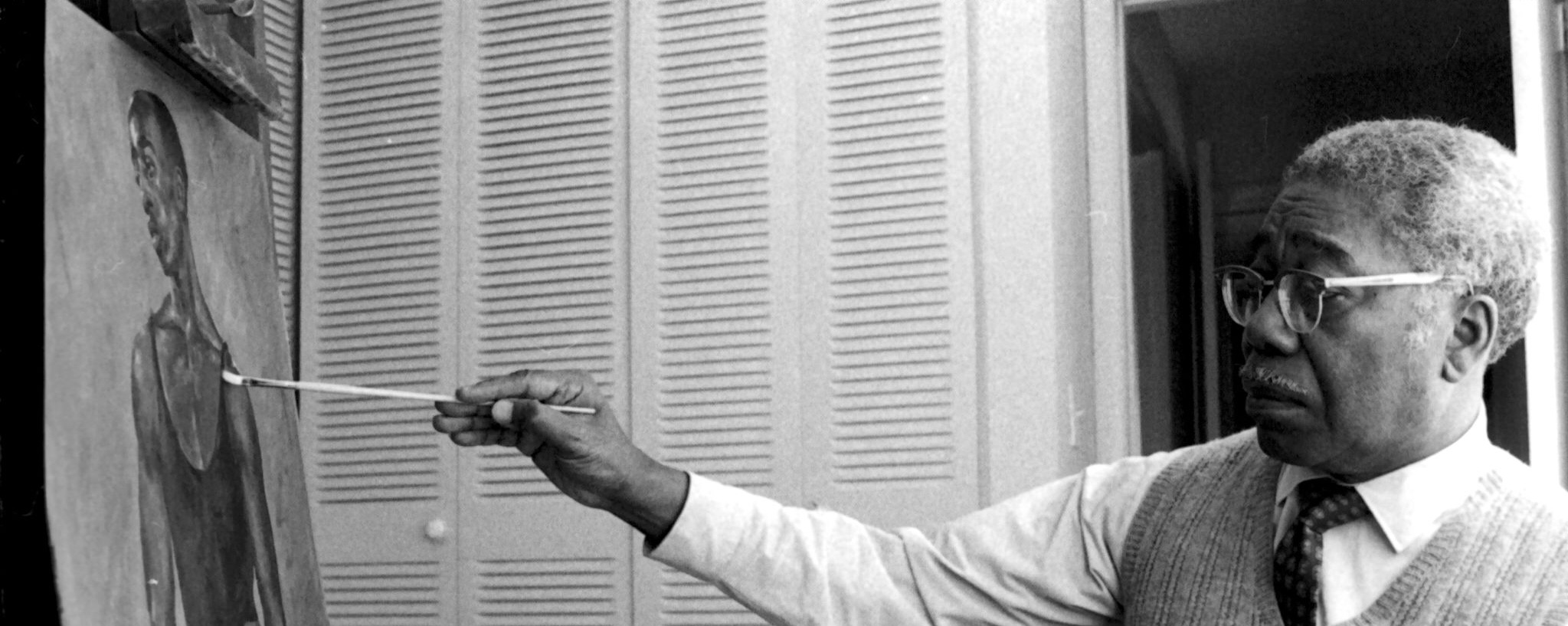

Aaron Douglas

(Robert Abbott Sengstacke, c.1970)

Courtesy of Getty Images

The most celebrated Harlem Renaissance artist is Aaron Douglas, often called as “the Father of Black American Art,”. Douglas had a unique artistic style that fused his interests in modernism and African art. He adapted African techniques to his paintings and murals, and book illustrations; his work proudly linked African-Americans with their heritage. His paintings are semi-abstract, two-dimensional, and geometrical, which was typical of the Art Deco style.

(Aaron Douglas, 1936)

Courtesy of National Gallery of Art

Douglas illustrated for the National Urban League’s magazine, and ‘The Crisis’, by the NAACP; two most important magazines of the Harlem Renaissance. He caught the attention of W.E.B. Du Bois and Dr. Alain Locke who were looking for young African American artists who championed African heritage in their art. He was commissioned to illustrate Locke’s publication ‘The New Negro’. His work soon became inspiration for future black artists. David C. Driskell, artist and scholar of African American art said, “At a time when it was unpopular to dignify the black image in white America, Douglas refused to compromise and see blacks as anything less than a proud and majestic people.”

“Do not call me the Father of African American Arts, for I am just a son of Africa, and paint for what inspires me.”

Aaron Douglas

James Van Der Zee

(Harry Hamburg/NY Daily News Archive, 1982)

Courtesy of Getty Images

Another notable figure is photographer James Van Der Zee. He is credited for chronicling the Harlem Renaissance with his photography. Van Der Zee gained a reputation for taking glamorous studio portraits. “He wanted to have his clients feel that they were looking handsome or beautiful,” his wife said. Van Der Zee’s sitters often brought their best clothes and copied celebrity poses and expressions, in the shoots.

In 1969 his photos were featured as part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition, ‘Harlem on My Mind’ , which showcased life during the Harlem Renaissance. Current black photographers and filmmakers such as Dawoud Bey, Jamel Shabazz, and Barry Jenkins have credited Van Der Zee as an inspiration.

Harlem Nightlife

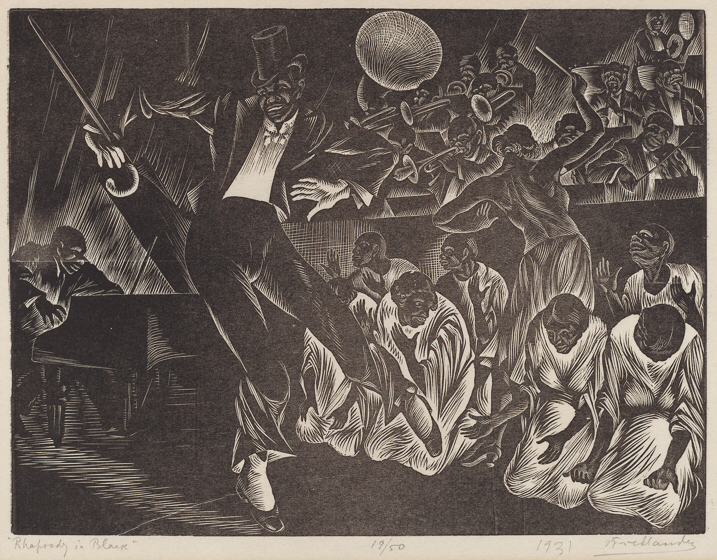

Jazz music became popular during the Harlem Renaissance and with it came a vibrant nightlife.

(George Rinhart/Corbis, c. 1920)

Courtesy of Getty Images

Jazz played at speakeasies offering illegal liquor, often accompanied by elaborate floor shows. The most successful of these was the Cotton Club. The less open-minded of the community disdained these clubs, while others believed they were a sign that black culture was moving towards acceptance.

Jazz became a great draw for not only Harlem residents, but outside white audiences also. The Savoy opened in 1927, it was an integrated ballroom with two bandstands that featured continuous jazz and dancing well past midnight. While it was fashionable to frequent Harlem nightlife, entrepreneurs realized that some white people wanted to experience black culture without having to socialize with African Americans and created clubs to cater to them.

Courtesy of Getty Images

As Harlem became one of the centers of jazz music, American fashion magazines pointed to its importance to New York nightlife, covering the popular nightclubs and the celebrities who performed there. By 1931 Vogue reported that ‘Every one can go to Harlem – and everyone does. You might almost say it was part of an American education to see the dusky high lights of Harlem’

Harlem was perceived as a place where one could throw caution to the wind and engage in unconstrained, immoral behavior. A guide to the nightlife of New York City in 1931 stated that Harlem, like Paris, ‘changes people. Especially the “proper” kind, once they get into its swing’.

(NY Daily News Archive, c.1920)

Courtesy of Getty Images

The Black Bottom, like the Charleston, was danced by African Americans in the South, before African American composer Perry Bradford introduced it in 1919 as a dance-song. Theatrical producer, George White saw the Black Bottom in Harlem in 1924 and had it adapted for his Broadway review Scandals of 1926, after which it became a dance craze. The Black Bottom incorporated savage, vulgar movements such as: slapping the backside with forward and backward hopping, feet stomping and pelvic gyrations. The Charleston and the Black Bottom were refined in order to suit the white American audience.

(Archive Photos, 1926)

Courtesy of Getty Images

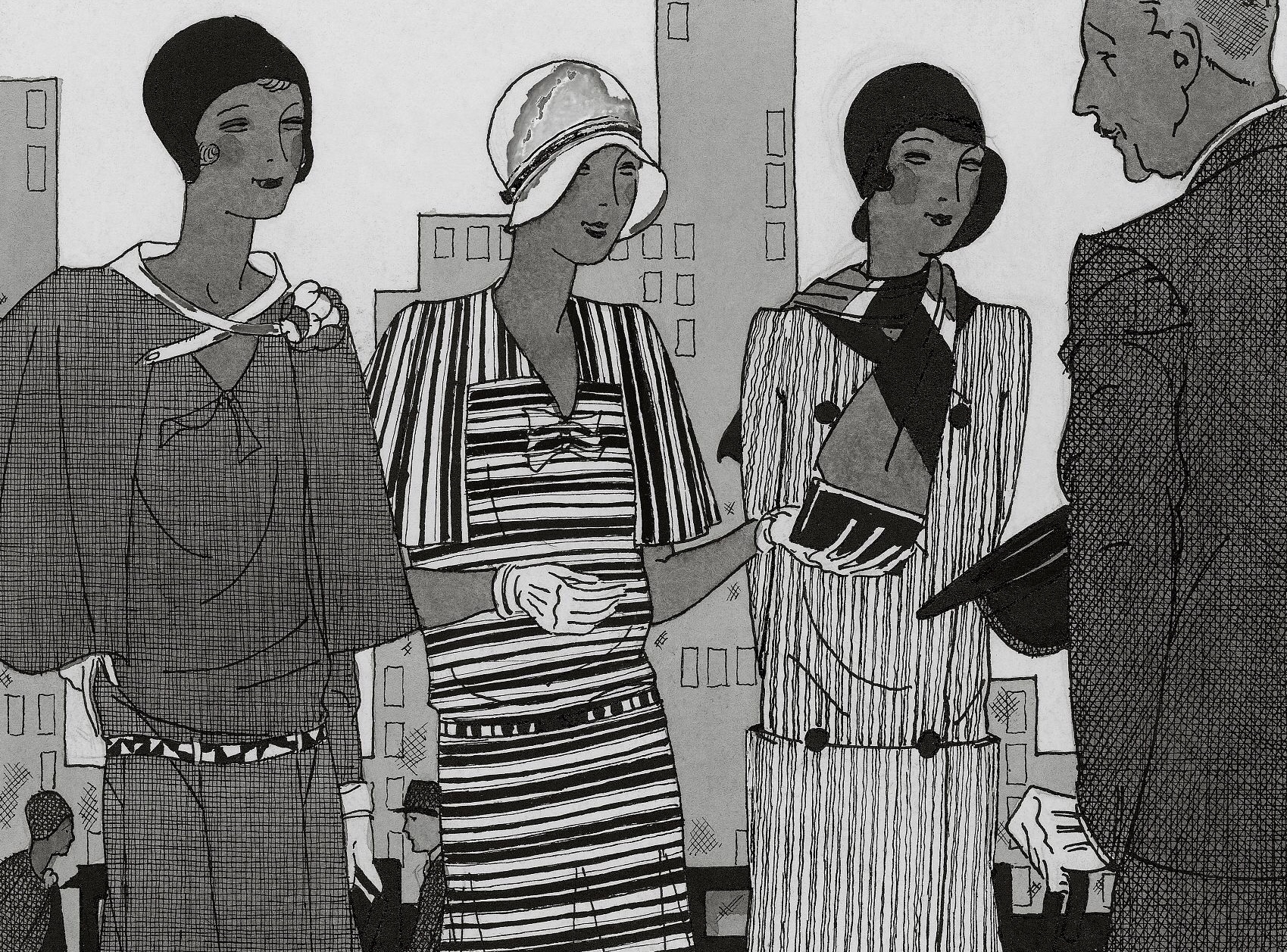

Fashion

The popularity of the Black Bottom and the Charleston influenced the fashion. By the mid 1920s dance dresses were short and often the arms were bare, to allow inhibited movement. A flapper who wore these scandalous dresses and danced the Charleston was seen as wild and untamed.

(Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis, c.1920)

Courtesy of Getty Images

French couturiere J. Suzanne Talbot designed a 1927 evening dress fringed and strung with wooden beads. The exposed legs and fringe echoed tribal African dress and, along with the percussion sound it created, exaggerated the primitive origins of the dance. The shortness of evening dresses for dancing in turn encouraged the shortening of day dresses.

Designer Paul Poiret, who was described as the father of the flapper movement, pointed to Jazz’s influence on French fashion, predicting that ‘the implacable and hypertrophic rhythms of the new dances, the blues and the Charleston, the din of unearthly instruments, and the musical idioms of exotic lands’ would lead to the androgyny later seen in women’s fashion. Women adapted men’s fashions to something with more grace and style suitable for a lady. Because of this new style, women created a new image of desirability.

(Illustration by Jean Pages/Condé Nast, 1929)

Courtesy of Getty Images

Summary

(James Van Der Zee, 1926)

Courtesy of National Gallery of Art

From my research, I gathered that the Harlem Renaissance did not solely break boundaries for African-Americans but western society in general. The freedom and primitive nature associated with Africans, and in-turn the Harlem Renaissance, influenced the western world to loosen their ideals of the ultimately civilised society, that the Victorians and Edwardians strived to achieve.

I believe World War One opened the new generations’ eyes to just how ruthless and uncivilised people could be, regardless of their race or class. They saw the need to enjoy life, while they had it, and to live it unapologetically. Women began to rebel and step out of the restricted mould the patriarchal environment put them in. Black people making a stand gave western women the courage to find their voice as well. They explored their sexuality and realised the impact they could create.

As the young generation partied in the integrated clubs they began to understand the thought of everyone, no matter their colour or gender, becoming equal members of the nation; making the Harlem Renaissance the foundation for our diverse and equal society.

Following the boundaries the Harlem Renaissance broke, it is almost as if society got scared of that much progress, leading to further enforcement of segregation.

The values and ideas the Harlem Renaissance created about equality were presented again in the Civil Rights Movement during the 50s and 60s. We saw Harlem Renaissance figures such as Josephine Baker come back, to finish what they started in the 20s. Fortunately, this time African Americans were able to achieve the justice they fought so long for.